History of Pythagoras

"Pythagoras of Samos" redirects here. For the Samian statuary, see Pythagoras (sculptor).

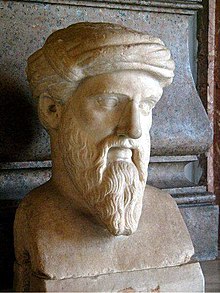

Pythagoras of Samos[a] (c. 570 – c. 495 BC)[b] was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of Plato, Aristotle, and, through them, Western philosophy. Knowledge of his life is clouded by legend, but he appears to have been the son of Mnesarchus, a gem-engraver on the island of Samos, then ruled by the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Modern scholars disagree regarding Pythagoras's education and influences, but they do agree that, around 530 BC, he travelled to Croton in southern Italy, where he founded a school in which initiates were sworn to secrecy and lived a communal, ascetic lifestyle. This lifestyle entailed a number of dietary prohibitions, traditionally said to have included vegetarianism, although modern scholars doubt that he ever advocated for complete vegetarianism.

The teaching most securely identified with Pythagoras is metempsychosis, or the "transmigration of souls", which holds that every soul is immortal and, upon death, enters into a new body. He may have also devised the doctrine of musica universalis, which holds that the planets move according to mathematical equations and thus resonate to produce an inaudible symphony of music. Scholars debate whether Pythagoras developed the numerological and musical teachings attributed to him, or if those teachings were developed by his later followers, particularly Philolaus of Croton. Following Croton's decisive victory over Sybaris in around 510 BC, Pythagoras's followers came into conflict with supporters of democracy and Pythagorean meeting houses were burned. Pythagoras may have been killed during this persecution, or escaped to Metapontum, where he eventually died.

In antiquity, Pythagoras was credited with many mathematical and scientific discoveries, including the Pythagorean theorem, Pythagorean tuning, the five regular solids, the Theory of Proportions, the sphericity of the Earth, and the identity of the morning and evening stars as the planet Venus. It was said that he was the first man to call himself a philosopher ("lover of wisdom")[c] and that he was the first to divide the globe into five climatic zones. Classical historians debate whether Pythagoras made these discoveries, and many of the accomplishments credited to him likely originated earlier or were made by his colleagues or successors. Some accounts mention that the philosophy associated with Pythagoras was related to mathematics and that numbers were important, but it is debated to what extent, if at all, he actually contributed to mathematics or natural philosophy.

Pythagoras influenced Plato, whose dialogues, especially his Timaeus, exhibit Pythagorean teachings. Pythagorean ideas on mathematical perfection also impacted ancient Greek art. His teachings underwent a major revival in the first century BC among Middle Platonists, coinciding with the rise of Neopythagoreanism. Pythagoras continued to be regarded as a great philosopher throughout the Middle Ages and his philosophy had a major impact on scientists such as Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton. Pythagorean symbolism was used throughout early modern European esotericism, and his teachings as portrayed in Ovid's Metamorphoses influenced the modern vegetarian movement.

Biographical sources

No authentic writings of Pythagoras have survived,[5][6][7] and almost nothing is known for certain about his life.[8][9][10] The earliest sources on Pythagoras's life are brief, ambiguous, and often satirical.[11][7][12] The earliest source on Pythagoras's teachings is a satirical poem probably written after his death by Xenophanes of Colophon, who had been one of his contemporaries.[13][14] In the poem, Xenophanes describes Pythagoras interceding on behalf of a dog that is being beaten, professing to recognize in its cries the voice of a departed friend.[15][13][12][16] Alcmaeon of Croton, a doctor who lived in Croton at around the same time Pythagoras lived there,[13] incorporates many Pythagorean teachings into his writings[17] and alludes to having possibly known Pythagoras personally.[17] The poet Heraclitus of Ephesus, who was born across a few miles of sea away from Samos and may have lived within Pythagoras's lifetime,[18] mocked Pythagoras as a clever charlatan,[11][18] remarking that "Pythagoras, son of Mnesarchus, practiced inquiry more than any other man, and selecting from these writings he manufactured a wisdom for himself—much learning, artful knavery."[18][11]

The Greek poets Ion of Chios (c. 480 – c. 421 BC) and Empedocles of Acragas (c. 493 – c. 432 BC) both express admiration for Pythagoras in their poems.[19] The first concise description of Pythagoras comes from the historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c. 484 – c. 420 BC),[20] who describes him as "not the most insignificant" of Greek sages[21] and states that Pythagoras taught his followers how to attain immortality.[20] The accuracy of the works of Herodotus are controversial.[22][23][24][25][26] The writings attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus of Croton, who lived in the late fifth century BC, are the earliest texts to describe the numerological and musical theories that were later ascribed to Pythagoras.[27] The Athenian rhetorician Isocrates (436–338 BC) was the first to describe Pythagoras as having visited Egypt.[20] Aristotle wrote a treatise On the Pythagoreans, which is no longer extant.[28] Some of it may be preserved in the Protrepticus. Aristotle's disciples Dicaearchus, Aristoxenus, and Heraclides Ponticus also wrote on the same subject.[29]

Most of the major sources on Pythagoras's life are from the Roman period,[30] by which point, according to the German classicist Walter Burkert, "the history of Pythagoreanism was already... the laborious reconstruction of something lost and gone."[29] Three lives of Pythagoras have survived from late antiquity,[30][10] all of which are filled primarily with myths and legends.[30][31][10] The earliest and most respectable of these is the one from Diogenes Laërtius's Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers.[30][31] The two later lives were written by the Neoplatonist philosophers Porphyry and Iamblichus[30][31] and were partially intended as polemics against the rise of Christianity.[31] The later sources are much lengthier than the earlier ones,[30] and even more fantastic in their descriptions of Pythagoras's achievements.[30][31] Porphyry and Iamblichus used material from the lost writings of Aristotle's disciples[29] and material taken from these sources is generally considered to be the most reliable.[29]

Life

Early life

Herodotus, Isocrates, and other early writers agree that Pythagoras was the son of Mnesarchus[33][20] and that he was born on the Greek island of Samos in the eastern Aegean.[33][5][34][35] His father is said to have been a gem-engraver or a wealthy merchant,[36][37] but his ancestry is disputed and unclear.[38][d] Pythagoras's name led him to be associated with Pythian Apollo (Pūthíā); Aristippus of Cyrene in the 4th century BC explained his name by saying, "He spoke [ἀγορεύω, agoreúō] the truth no less than did the Pythian [πυθικός puthikós]".[39] A late source gives Pythagoras's mother's name as Pythaïs.[40][41] Iamblichus tells the story that the Pythia prophesied to her while she was pregnant with him that she would give birth to a man supremely beautiful, wise, and beneficial to humankind.[39] As to the date of his birth, Aristoxenus stated that Pythagoras left Samos in the reign of Polycrates, at the age of 40, which would give a date of birth around 570 BC.[42]

During Pythagoras's formative years, Samos was a thriving cultural hub known for its feats of advanced architectural engineering, including the building of the Tunnel of Eupalinos, and for its riotous festival culture.[43] It was a major center of trade in the Aegean where traders brought goods from the Near East.[5] According to Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier, these traders almost certainly brought with them Near Eastern ideas and traditions.[5] Pythagoras's early life also coincided with the flowering of early Ionian natural philosophy.[44][33] He was a contemporary of the philosophers Anaximander, Anaximenes, and the historian Hecataeus, all of whom lived in Miletus, across the sea from Samos.[44]

Alleged travels

Pythagoras is traditionally thought to have received most of his education in Ancient Egypt, the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the Achaemenid Empire, and Crete .[45] Modern scholarship has shown that the culture of Archaic Greece was heavily influenced by those of Levantine and Mesopotamian cultures.[45] Like many other important Greek thinkers, Pythagoras was said to have studied in Egypt.[46][20][47] By the time of Isocrates in the fourth century BC, Pythagoras's alleged studies in Egypt were already taken as fact.[39][20] The writer Antiphon, who may have lived during the Hellenistic Era, claimed in his lost work On Men of Outstanding Merit, used as a source by Porphyry, that Pythagoras learned to speak Egyptian from the Pharaoh Amasis II himself, that he studied with the Egyptian priests at Diospolis (Thebes), and that he was the only foreigner ever to be granted the privilege of taking part in their worship.[48][45] The Middle Platonist biographer Plutarch (c. 46 – c. 120 AD) writes in his treatise On Isis and Osiris that, during his visit to Egypt, Pythagoras received instruction from the Egyptian priest Oenuphis of Heliopolis (meanwhile Solon received lectures from a Sonchis of Sais).[49] According to the Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215 AD), "Pythagoras was a disciple of Soches, an Egyptian archprophet, as well as Plato of Sechnuphis of Heliopolis."[50] Some ancient writers claimed, that Pythagoras learned geometry and the doctrine of metempsychosis from the Egyptians.[46][51]

Other ancient writers, however, claimed that Pythagoras had learned these teachings from the Magi in Persia or even from Zoroaster himself.[52][53] Diogenes Laërtius asserts that Pythagoras later visited Crete, where he went to the Cave of Ida with Epimenides.[52] The Phoenicians are reputed to have taught Pythagoras arithmetic and the Chaldeans to have taught him astronomy.[53] By the third century BC, Pythagoras was already reported to have studied under the Jews as well.[53] Contradicting all these reports, the novelist Antonius Diogenes, writing in the second century BC, reports that Pythagoras discovered all his doctrines himself by interpreting dreams.[53] The third-century AD Sophist Philostratus claims that, in addition to the Egyptians, Pythagoras also studied under Hindu sages in India.[53] Iamblichus expands this list even further by claiming that Pythagoras also studied with the Celts and Iberians.[53]

Alleged Greek teachers

Ancient sources also record Pythagoras having studied under a variety of native Greek thinkers.[53] Some identify Hermodamas of Samos as a possible tutor.[55][53] Hermodamas represented the indigenous Samian rhapsodic tradition and his father Creophylos was said to have been the host of his rival poet Homer.[53] Others credit Bias of Priene, Thales,[56] or Anaximander (a pupil of Thales).[56][57][53] Other traditions claim the mythic bard Orpheus as Pythagoras's teacher, thus representing the Orphic Mysteries.[53] The Neoplatonists wrote of a "sacred discourse" Pythagoras had written on the gods in the Doric Greek dialect, which they believed had been dictated to Pythagoras by the Orphic priest Aglaophamus upon his initiation to the orphic Mysteries at Leibethra.[53] Iamblichus credited Orpheus with having been the model for Pythagoras's manner of speech, his spiritual attitude, and his manner of worship.[58] Iamblichus describes Pythagoreanism as a synthesis of everything Pythagoras had learned from Orpheus, from the Egyptian priests, from the Eleusinian Mysteries, and from other religious and philosophical traditions.[58] Riedweg states that, although these stories are fanciful, Pythagoras's teachings were definitely influenced by Orphism to a noteworthy extent.[59]

Of the various Greek sages claimed to have taught Pythagoras, Pherecydes of Syros is mentioned most often.[60][59] Similar miracle stories were told about both Pythagoras and Pherecydes, including one in which the hero predicts a shipwreck, one in which he predicts the conquest of Messina, and one in which he drinks from a well and predicts an earthquake.[59] Apollonius Paradoxographus, a paradoxographer who may have lived in the second century BC, identified Pythagoras's thaumaturgic ideas as a result of Pherecydes's influence.[59] Another story, which may be traced to the Neopythagorean philosopher Nicomachus, tells that, when Pherecydes was old and dying on the island of Delos, Pythagoras returned to care for him and pay his respects.[59] Duris, the historian and tyrant of Samos, is reported to have patriotically boasted of an epitaph supposedly penned by Pherecydes which declared that Pythagoras's wisdom exceeded his own.[59] On the grounds of all these references connecting Pythagoras with Pherecydes, Riedweg concludes that there may well be some historical foundation to the tradition that Pherecydes was Pythagoras's teacher.[59] Pythagoras and Pherecydes also appear to have shared similar views on the soul and the teaching of metempsychosis.[59]

Before 520 BC, on one of his visits to Egypt or Greece, Pythagoras might have met Thales of Miletus, who would have been around fifty-four years older than him. Thales was a philosopher, scientist, mathematician, and engineer,[61] also known for a special case of the inscribed angle theorem. Pythagoras's birthplace, the island of Samos, is situated in the Northeast Aegean Sea not far from Miletus.[62] Diogenes Laërtius cites a statement from Aristoxenus (fourth century BC) stating that Pythagoras learned most of his moral doctrines from the Delphic priestess Themistoclea.[63][64][65] Porphyry agrees with this assertion,[66] but calls the priestess Aristoclea (Aristokleia).[67] Ancient authorities furthermore note the similarities between the religious and ascetic peculiarities of Pythagoras with the Orphic or Cretan mysteries,[68] or the Delphic oracle.[69]

In Croton

Porphyry repeats an account from Antiphon, who reported that, while he was still on Samos, Pythagoras founded a school known as the "semicircle".[70][71] Here, Samians debated matters of public concern.[70][71] Supposedly, the school became so renowned that the brightest minds in all of Greece came to Samos to hear Pythagoras teach.[70] Pythagoras himself dwelled in a secret cave, where he studied in private and occasionally held discourses with a few of his close friends.[70][71] Christoph Riedweg, a German scholar of early Pythagoreanism, states that it is entirely possible Pythagoras may have taught on Samos,[70] but cautions that Antiphon's account, which makes reference to a specific building that was still in use during his own time, appears to be motivated by Samian patriotic interest.[70]

Around 530 BC, when Pythagoras was around forty years old, he left Samos.[33][72][5][73][74] His later admirers claimed that he left because he disagreed with the tyranny of Polycrates in Samos,[61][72] Riedweg notes that this explanation closely aligns with Nicomachus's emphasis on Pythagoras's purported love of freedom, but that Pythagoras's enemies portrayed him as having a proclivity towards tyranny.[72] Other accounts claim that Pythagoras left Samos because he was so overburdened with public duties in Samos, because of the high estimation in which he was held by his fellow-citizens.[75] He arrived in the Greek colony of Croton (today's Crotone, in Calabria) in what was then Magna Graecia.[76][33][77][74] All sources agree that Pythagoras was charismatic and quickly acquired great political influence in his new environment.[78][33][79] He served as an advisor to the elites in Croton and gave them frequent advice.[80] Later biographers tell fantastical stories of the effects of his eloquent speeches in leading the people of Croton to abandon their luxurious and corrupt way of life and devote themselves to the purer system which he came to introduce.[81][82]

Family and friends

Diogenes Laërtius states that Pythagoras "did not indulge in the pleasures of love"[86] and that he cautioned others to only have sex "whenever you are willing to be weaker than yourself".[87] According to Porphyry, Pythagoras married Theano, a lady of Crete and the daughter of Pythenax[87] and had several children with her.[87] Porphyry writes that Pythagoras had two sons named Telauges and Arignote,[87] and a daughter named Myia,[87] who "took precedence among the maidens in Croton and, when a wife, among married women."[87] Iamblichus mentions none of these children[87] and instead only mentions a son named Mnesarchus after his grandfather.[87] This son was raised by Pythagoras's appointed successor Aristaeus and eventually took over the school when Aristaeus was too old to continue running it.[87] Suda writes that Pythagoras had 4 children (Telauges, Mnesarchus, Myia and Arignote).[88]

The wrestler Milo of Croton was said to have been a close associate of Pythagoras[89] and was credited with having saved the philosopher's life when a roof was about to collapse.[89] This association may been the result of confusion with a different man named Pythagoras, who was an athletics trainer.[70] Diogenes Laërtius records Milo's wife's name as Myia.[87] Iamblichus mentions Theano as the wife of Brontinus of Croton.[87] Diogenes Laërtius states that the same Theano was Pythagoras's pupil[87] and that Pythagoras's wife Theano was her daughter.[87] Diogenes Laërtius also records that works supposedly written by Theano were still extant during his own lifetime[87] and quotes several opinions attributed to her.[87] These writings are now known to be pseudepigraphical.[87]

Death

Pythagoras's emphasis on dedication and asceticism are credited with aiding in Croton's decisive victory over the neighboring colony of Sybaris in 510 BC.[90] After the victory, some prominent citizens of Croton proposed a democratic constitution, which the Pythagoreans rejected.[90] The supporters of democracy, headed by Cylon and Ninon, the former of whom is said to have been irritated by his exclusion from Pythagoras's brotherhood, roused the populace against them.[91] Followers of Cylon and Ninon attacked the Pythagoreans during one of their meetings, either in the house of Milo or in some other meeting-place.[92][93] Accounts of the attack are often contradictory and many probably confused it with later anti-Pythagorean rebellions.[91] The building was apparently set on fire,[92] and many of the assembled members perished;[92] only the younger and more active members managed to escape.[94]

Sources disagree regarding whether Pythagoras was present when the attack occurred and, if he was, whether or not he managed to escape.[32][93] In some accounts, Pythagoras was not at the meeting when the Pythagoreans were attacked because he was on Delos tending to the dying Pherecydes.[93] According to another account from Dicaearchus, Pythagoras was at the meeting and managed to escape,[95] leading a small group of followers to the nearby city of Locris, where they pleaded for sanctuary, but were denied.[95] They reached the city of Metapontum, where they took shelter in the temple of the Muses and died there of starvation after forty days without food.[95][32][92][96] Another tale recorded by Porphyry claims that, as Pythagoras's enemies were burning the house, his devoted students laid down on the ground to make a path for him to escape by walking over their bodies across the flames like a bridge.[95] Pythagoras managed to escape, but was so despondent at the deaths of his beloved students that he committed suicide.[95] A different legend reported by both Diogenes Laërtius and Iamblichus states that Pythagoras almost managed to escape, but that he came to a bean field and refused to run through it, since doing so would violate his teachings, so he stopped instead and was killed.[97][95] This story seems to have originated from the writer Neanthes, who told it about later Pythagoreans, not about Pythagoras himself.[95

Comments

Post a Comment